Jacqueline Passmore is an award-winning artist, director, and producer whose work spans a vast spectrum of moving image artforms. Based in London, but with roots in the American South and Sámi heritage, Passmore’s journey has taken her around the globe, creating visual and sensory experiences that challenge and captivate audiences. Her films, installations, and live video performances invite us to explore large-scale narratives through the lens of empathy, perception, and abstraction. Passmore’s work has been featured by world-renowned institutions such as Tate Modern, Berlinale Talents, and the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA). She has collaborated with major designers, architects, and musicians, including Zaha Hadid Architects, Stereolab, and Ladytron.

With a diverse background that includes studying film production in Austin, Texas, and photography in New York City, her artistic vision is informed by her distinct sensory sensibility and technical prowess.

In this interview, Jacqueline shares insights into her creative journey—from her early fascination with Robert Frank’s photography to her groundbreaking performances on international music tours. She opens up about her experiences working in different countries, how her personal life and creative work nourish each other, and the ongoing evolution of her creative vision. Whether it’s her love for the interconnection of film and music or her commitment to fostering new voices in the screen industries, Passmore’s story is a masterclass in artistic resilience, collaboration, and innovation.

Jacqueline Passmore Q&A

Can you share a bit about your journey as a creative? What first sparked your interest in the visual arts and filmmaking?

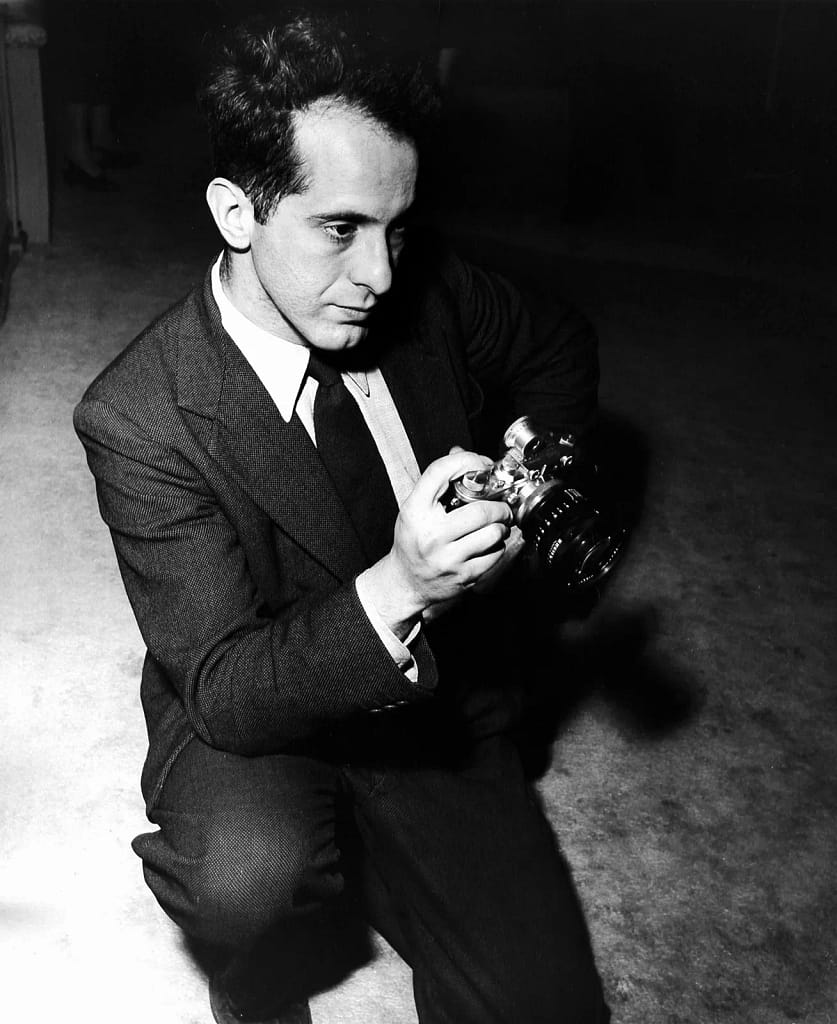

When I was 13, I got a copy of Robert Frank’s The Americans – a collection of photos he took across the USA in the 50s, as a new immigrant. I instantly understood the role of the gaze in photography and film – that we literally inhabit the artist’s worldview. There is something in the soulfulness and emotional timbre of Robert Frank’s outsider view that resonated with me so distinctly, as a young person growing up in the American South.

It’s a mistake to assume young people don’t appreciate the nuances of art. I think kids are often more sensitive to creative expression, specifically because they don’t yet have the autonomy to give voice to their observations.

I got deeply into 35mm photography in high school and built a darkroom in my bathroom, where I started experimenting with photographic techniques. I scratched my negatives, I wrote on them, I coated objects with Liquid Light emulsion and printed photos onto them. I wanted my photos to do more, so when I shifted into filmmaking, it felt natural. I saw filmmaking as photography with the added dimensions of time and sound.

At 18 I got into an Honours film programme in Austin, one of very few women. We were the last year to train on 16mm film as well as digital video, so I learned all those analogue processes.

Austin was the coolest town in those days, with a remarkable experimental film and music community. Outside of class, I started working with an amazing group of filmmakers led by Athina Rachel Tsangari and David Barker, who ran a film festival called Cinematexas. Cinematexas punched so far above its weight that it rose to international significance almost overnight. It commissioned some of the earliest performances by Miranda July, and featured work by artists like Anthony McCall and Rosa Barba. A lot of us were so young that we didn’t see any barrier to picking up a phone and approaching anyone we thought was cool, so we just went for it. I think our excitement had its own momentum.

I learned so much by being exposed to such high calibre expanded cinema work, and meeting so many indie filmmakers, artists, and curators. I started making my own work and getting it shown in exhibitions, emboldened by learning firsthand that there was a serious place in the world for moving image art.

How has your creative vision evolved over the years, particularly with the diverse experiences you’ve had in different places?

I’ve always been fascinated by abstraction as a visual language, moments of emotional ignition, and films that tell large stories sparingly. I love the spark of the cognitive shift, when we connect with people in shared understanding, beyond the spoken word. Real life is epic, real life is large- scale, real life is orchestral. When I look at my trajectory, I can see that my desire to connect and communicate with people on that elemental level is a recurrent theme in my life, and in my work.

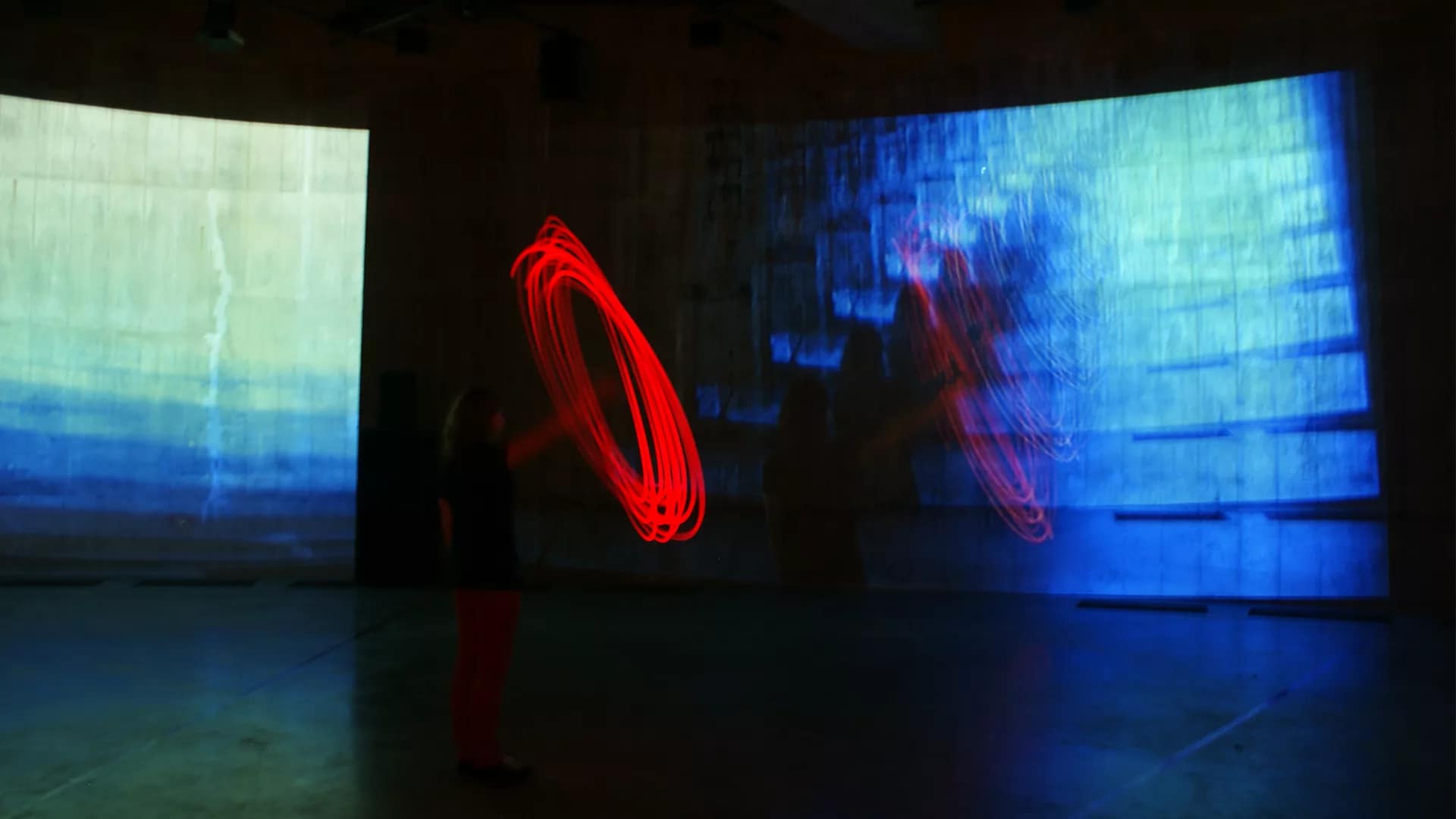

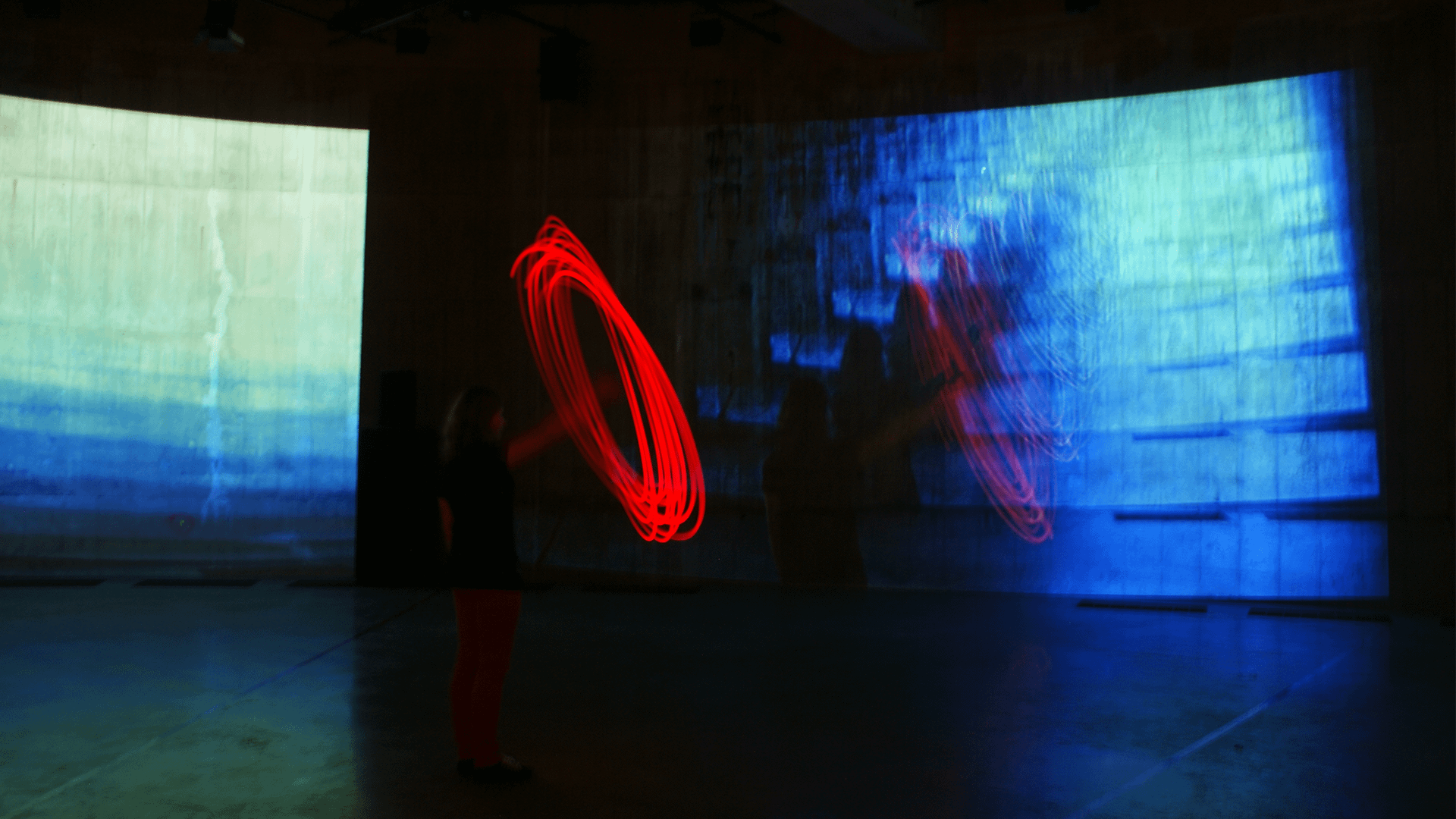

In my early 20s, I packed up my exhibition catalogues and went to the British Consulate in LA, where I applied to immigrate to England as an artist. I was accepted. It was an amazing, rare opportunity, but my visa also meant I could only accept work as an artist in the UK, a rigid constraint for anyone. It was sink or swim, so I swam as hard as I could. I had my first video piece commissioned by FACT in Liverpool, and I shortly fell in with a really cool group of Liverpool musicians, including the female-fronted band Ladytron. I started making live performances of my own hand-manipulated films, performing live on international tours first with Ladytron, and then with musicians like Anglo-French band Stereolab.

As a moving image artist, I approach video performances as living films that I re-edit every night, in an intimate call and response to the music. Filmmakers never get the opportunity to engage with audiences in that reflexive way. I learned so much as a filmmaker during my years of world tours, especially about the shared sensory communion of mass audiences. As my projected film works got physically larger in scale, I started receiving bigger commissions for gallery-based video installations, and increasingly substantial commissions for my directorial film work. It’s easy to see the thread of conceptual connection looking back, but life is only lived forwards. As artists, I think we have to trust that the thread is unbreakable, and continuously challenge ourselves to take the next, bravest steps as they appear.

As a professional creative, what does a typical day look like for you? How do you maintain a balance between inspiration and the business side of your work and personal life.

I keep similar rhythms, wherever I am. It’s grounding to have consistency. I rearrange hotel rooms, I unpack my bags. I create a feeling of home wherever I am in the world. It’s a rare day I’m not up by 6 a.m. Film shoots start early, so I’m hard-wired now – but also morning is the best time of the day.

If I’m home, I have a walk early morning. It’s a gift to have access to a wild park in central London. The area I live in has long attracted artists, and I’m fascinated by it. Paul Robeson, Daphne du Maurier, Lázsló Moholy-Nagy, Nick Drake, and Peter Cook all lived within a tiny radius. I stop for coffee and people watch and make my lists. A lot of my work is solo, so I love seeing people early in the day.

From mid-morning I’m working, whether that’s in the studio, on an edit, or in meetings. It’s counter- intuitive, but it’s discipline that gives us artistic freedom. You’ve got to build a structure for yourself that holds the hours you need to think and work.

My biggest indulgence is my love of the cinema. I see 2 – 3 films a week. Often, it’s just me and a few older film buffs. Part of it is research, but cinemas are also sacred spaces for me. Like live music, I love that cinemas allow introverts to be alone together, sharing a profound experience. I love that feeling of reemerging back into the light of day, having been transported.

Who or what are some of your biggest influences, whether they be artists, filmmakers, or life experiences?

Music rules my life – as with movies, music has always been my proof of a larger world. I was heavily into British music as a kid. I had older, cooler friends who got me in to see bands like Portishead and the Jesus & Mary Chain when I was underage (bless them). I’m also a devoted fan of British cinema, from Alan Clarke to Andrea Arnold. The link between film and music is inextricable; I love how many British lyricists can build entire narratives in 3 minutes. Squeeze’s “Up The Junction” is a perfect film, delivered as a pop song.

I’m moved by how open British cinema is to distinct voices. When you scratch the surface, so many pioneering British filmmakers view the culture from a peripheral perspective, like Karel Reisz (director of Saturday Night and Sunday Morning), who was a Czech child refugee who arrived on the Kindertransport, only to become integral in creating the most British of genres, the Kitchen Sink drama. This multifaceted aspect of the British cinematic voice is consistently fascinating to me. It also harks back to the same outsider viewpoint I valued in Robert Frank’s The Americans, or British photographer Tish Murtha’s observations of working-class Northern kids in the 70s. Like hearing a certain frequency, it’s peripheral voices I pick up on; perhaps because I have one.

So many artists have impacted me, from the Vasulkas to Wim Wenders, but my friends and contemporaries interest me most. My husband (songwriter Howie Payne) is the light of my life. I don’t make music, so to be so close to someone who creates it from thin air is like witnessing alchemy. We all accept the idea of women as muses to men, but we rarely talk about men as creatively inspiring to women. However, I live that, daily.

I take great inspiration from my friends who work in interdisciplinary ways. My sister-in-law Candie Payne is an uber cool singer-songwriter and an exceptional visual artist. My friend Reuben Wu is a prolific artist photographer who was also a founding member of Ladytron. When we toured together, Reuben always took expansive photos of landscapes, wherever we were in the world. To witness his work evolve over time has been really moving. I first met my friend Emma Richardson through her soaring, symphonic paintings, and she also plays bass in the Pixies. I get really excited by people whose will to create isn’t limited to a single medium.

British-based artists I love include Imogen Stidworthy, who is a person of great substance. Thandi Loewenson is phenomenal. Rebecca Lennon is whip smart. I adore Kim Pace. Gaby Sahhar has been on my radar since they were a teenager. I admire gallerist Robin Klassnik, whose Matt’s Gallery has exhibited a lot of my friends’ work. His taste always interests me.

For me, Carol Morley is the most compelling British filmmaker operating right now. She has such a light-handed, erudite and compassionate approach to the complexities of human nature, and large issues like classism. She makes me excited to work in film.

What role does collaboration play in your work? Can you share an example of a collaborative project that significantly impacted your creative process?

Filmmaking is a discipline that teaches you to value the whole crew; everyone has a defined role and everyone is vital. I think one reason I’ve had such fruitful collaborations is that I genuinely believe in other people and their superpowers.

One of my favorite collaborations has been my work performing live video visuals on tour with Stereolab. I have immense respect for them as artists. I’ve loved the band since I was a teenager, but I came away an even bigger fan, even after countless performances.

What are some of the most rewarding aspects of having a career in the creative industry? Are there any challenges you frequently encounter?

Generosity makes us part of something larger than ourselves. The film industry can be very transactional, and that’s not my nature. I believe in paying it forward. If you spot someone with talent, never hesitate to align them with opportunity. The universe loves efficiency, and if you can be the direct line between two points, you’re doing good work. My friend the curator/artist mentor Ceri Hand says it’s not enough to hold the door open behind you, you have to actively bring people with you. I believe that.

There have been times when the work has given back to me, which utterly surprised me. I love working with people in socially engaged practice, and I’ve done tonnes of arts outreach work with underserved communities. Several years ago I was approached to design an experimental arts programme for mental health in-patients for the NHS. It was out of my comfort zone, and I had to

do a lot of training. It wound up being one of the most rewarding experiences of my life. Nothing has taught me more about compassion, and what it means to be a human being.

For those considering a career in the creative field, what advice would you give them? What qualities do you think are essential for success?

People will commission you because the work is good, but they will recommend you based on how you handle yourself. Did you deliver? Did you treat everyone with respect? Those are the two big questions, and they’re of equal value.

The creative industries value the auteur. People want to believe in you, your story, and your artistic vision. While you’ve got to be confident that your viewpoint is valid, it’s also very important never to assume you’re the smartest person in the room. If you’re lucky, you’ll find yourself in rooms with increasing numbers of brilliant people. Value them and learn everything you can from them.

Can you tell us about any current or upcoming projects that you’re particularly excited about? What can we expect to see from you in the near future?

I’ve just launched a really exciting collaboration called Passmore Locher, working in partnership with my friend Heidi Locher. Heidi is an incredibly talented and revered British architect who has been called “a quiet kind of living legend.” As a filmmaker and an architect, we’re making installation art that explores conceptual crossovers between cinema and architecture. It’s exhilarating for me, not just because Heidi is a fearless and visionary artist, but also because Heidi is the coolest woman I know. Heidi will keep designing buildings, and I’ll keep making films, and we come together to explore the most stimulating shared concepts.

I’m super excited about my own upcoming film project, and my work with Passmore Locher. Both will be premiering in 2025.

How do you see the role of visual arts and filmmaking evolving in the coming years, especially with the rise of digital media and new technologies?

I’ve always considered teaching to be a political act; I love lecturing and talking about how films work. As a young woman, I wasn’t treated like a contender in technical conversations, so when I discovered I had high technical aptitude in film school, it was game changing. Unlocking that in other people is meaningful.

Filmmaking has long cultivated a culture of technical exclusivity, because as filmmakers our livelihoods are linked to the rarity of our expertise. However, in this age of media saturation, we benefit more as a society from everyone cultivating the basic technical and critical thinking skills required to decode and question media. And hopefully to use those tools with increasing compassion and consideration for their power.

Years ago I saw Le Tigre play, and their backdrop read “Behind the hysteria of male expertise lies the magic world of our unmade art”. You can use “male” in that statement, but you can also use any other dominant descriptor that applies for you, or simply “expertise”. So many doors open when we invite ourselves into the conversation and start asking how things work. Those questions ultimately benefit filmmaking as an art, and society as a whole – they prompt the really big questions – about representation, narrative voice and gaze, and image construction.

In my own career, change is the only constant I’ve witnessed in technology. When it comes to new creative tools, instead of defaulting to fear, I think we have to take the wide view and ask, what positives do they have to contribute?

Where can our readers find more of your work? Please share any websites, social media handles, or upcoming exhibitions.

I’m on IG as @jac_passmore

My website is www.jacquelinepassmore.com

Credits: Image of Robert Frank – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Frank.

Images of Jacqueline (Portrait) photo – Beau de Palma.

Jaqueline Passmore / Feedback Loops at Tate Modern, Photo Joshua Bradwell.